Chapter Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has provided a ‘stress test’ for occupational safety and health in the EU, unfortunately revealing several structural deficiencies in the regulatory system.

In 2020, many workers found themselves exposed to the SARS-CoV-2 virus and its related psychosocial risks. This collective experience has been powerful testimony to significant failures in the implementation of preventive occupational health and safety (OSH) measures across the board. If the Covid-19 crisis has made one thing clear, it is the importance of OSH as a central issue in the world of work.

OSH is one of the fields of law with a strong European basis. The 1989 ‘Framework Directive on the introduction of measures to encourage improvements in the safety and health of workers at work’ (89/391/EEC) lays down the key principles that underpin EU occupational health and safety regulation. Vogel (2015) refers to the Directive as ‘the benchmark law’ in his historical, legal and institutional overview ‘The machinery of occupational safety and health policy in the European Union’.

The 1989 Framework Directive places preventive measures at the heart of occupational health and safety regulation and emphasises collective measures over individual ones. It requires all workers to be protected equally by health and safety law, regardless of their status. It lays down the legal responsibility of employers to provide healthy and safe workplaces, and the right of workers to be consulted on their working conditions.

A total of 22 so-called ‘daughter directives’, issued under the Framework Directive, cover different risk factors and different categories of workers and provide more specific rules based on the principles enshrined in Directive 89/391. One of these directives is Directive 2000/54/EC, the Biological Agents Directive. This is the first instrument against which we benchmark what this chapter identifies as a fundamental failure on the part of the EU in dealing with the pandemic: the (mis-)classification of SARS-CoV-2 as a relatively lower-risk (group 3) biological agent. According to a proper application of the Directive’s classification rules, it would have been appropriate for the virus to be included in the higher-risk group 4.

The first section of this chapter identifies the long-existing poor classification practices that have led the Commission to undervalue the risk level of the virus that has caused the Covid-19 pandemic. Moreover, it identifies some deficiencies in the Directive itself, most notably the absence of a notion of a pandemic situation. The following section explores the impact of the pandemic on the healthcare sector and argues that much of the strain experienced by the sector and by its workforce is the consequence of chronic underfunding and deteriorating working conditions in hospitals and care homes, and of resulting staff shortages. The third section offers a nuanced assessment of the contribution that digitally-mediated work has made with regard to gig workers during the pandemic. It notes that, far from emerging as the panacea that would have allowed everyone to earn an income while socially distancing, gig work has shown the limits arising from inadequate coverage by the regulatory framework, thereby exposing millions of vulnerable workers – the so-called ‘bogus self-employed’ – to a heightened level of hazards, both old and new. The fourth and fifth sections of this chapter highlight the adverse impact that the pandemic has had on the safety and health of particular groups, such as women and ethnic minority workers, that tend to be overrepresented in a number of frontline services and occupations. These latter sections identify the exponential growth of psychosocial risks for these workers, and for low-income workers at large, as a key area of concern; this analysis is partly based on research recently carried out on behalf of the ETUI by a group of VUB researchers.

Staffing shortages in the healthcare sector: part of the problem

Staffing shortages, especially of nurses, have been identified as one of the major factors constraining hospitals' ability to deal with infection outbreaks (Stone et al. 2004). As early as 2012, the European Commission estimated that the gap in human resources in healthcare in the EU would be approximately 1,000,000 health professionals by 2020 , among which 590,000 would be nurses (European Commission 2012). In spite of these early warnings, little progress has been made in addressing these anticipated deficiencies. On 7 April 2020 – World Health Day, dedicated this year to nurses and midwives – the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reported a continuing strain on health and social care systems and healthcare workers, highlighting staff shortages due to increased demand and high rates of staff infection with Covid-19. On the same day, a team of European doctors and nurses from Romania and Norway, deployed through the EU Civil Protection Mechanism, was dispatched to Milan and Bergamo to help Italian medical staff battling the coronavirus. A swift emergency response and an uplifting gesture of solidarity, certainly, but not a sustainable long-term strategy, especially as what health systems are really in need of are staff to provide the care that was postponed during the first wave of the pandemic. On 20 May 2020, the EC adopted proposals for country-specific recommendations that highlighted issues with both working conditions for doctors and nurses and shortages of health workers. All countries were recommended to ‘strengthen the resilience of their health systems’; for 20 Member States there is a direct reference to the health workforce (European Commission 2020b).

The shortage of nurses and care personnel in the EU is structurally linked to imbalances between the growing demand for healthcare services and the declining or inadequate workforce supply. Factors responsible for increased demand include a stable rise in chronic diseases and an aging population; at the start of 2018 almost one fifth (19.7 %) of the total population was 65 years or older. Over the next three decades, the number of older people in the EU is projected to follow an upward path towards a relative share of the total population of 28.5% by 2050 (Eurostat 2019). Factors responsible for decreased supply include an aging workforce, staff turnover, work-related sick leave, and students dropping out of training. Covid-19 has only exacerbated these pre-existing issues.

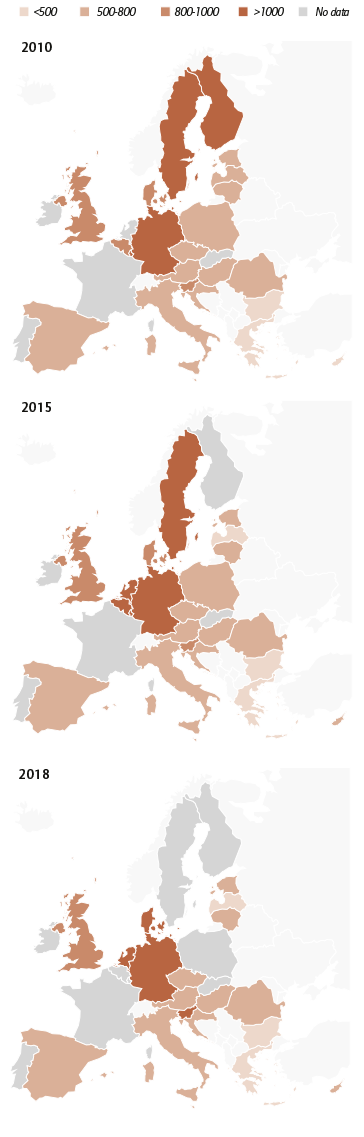

Figure 5.2. Symbol map of nurses per 100 000 inhabitants in the EU Member States in 2010, 2015 and 2018. Source: Eurostat, ‘Healthcare personnel statistics - nursing and caring professionals'

Source: Eurostat, nursing and caring professionals

The number of practising nursing professionals relative to population size fell in nine EU Member States between 2012 and 2017 (Eurostat 2020). The number of nurses per 100,000 inhabitants in 2018 was over 1,000 in Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Slovenia. The lowest numbers (fewer than 500 nurses per 100,000 inhabitants) were observed in Bulgaria, Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, and Latvia. In the UK, where there are just under 778 nurses per 100,000 inhabitants, nurses are placed in the ‘shortage occupation’ list, as a role ‘experiencing significant shortages’ (Nuffield Trust 2020). In Finland, the Ministry of Labour’s Occupational Barometer of 18 September 2020 highlights that the shortages of skilled labour in the healthcare and social work professions is now higher than ever (TEM 2020). In Italy and Spain, where nursing shortages had already been flagged up, the Covid-19 pandemic hit the health systems hard. Chronically low levels of public spending have greatly contributed to inadequate numbers of healthcare personnel, especially nurses, and it is estimated that Italy would need between 53,000 and 54,000 more nurses to reach the European average. In Spain, meanwhile. the shortfall is estimated to be between 88,000 and 125,000 (European Data Journalism Network 2020).

Filling such shortages requires targeted measures in the years to come, partly to overcome what in many ways appears to be a fully-fledged vocational crisis for certain occupations in the sector. A 2013 cross-sectional survey of 33,659 hospital nurses (medical and surgical) in 12 European countries (Belgium, England, Finland, Germany, Greece, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland) reported that 19-49% of nurses intended to leave their jobs that year (Aiken et al. 2013). It is anticipated that the Covid-19 pandemic will only reinforce these sentiments.

Staffing shortages create immediate occupational safety and health risks for health workers and patients and result in long-lasting negative consequences for health systems. Conversely, and from a preventative OSH perspective, adequate nurse-to-patient staffing reduces occupational injury and illness rates (KCE 2019). The current growing shortage of personnel, and the limited resources available in healthcare systems, are resulting in an inability to meet local demands for healthcare, which in turn increases the risk of violence and harassment against workers from third parties (such as patients and their relatives). Furthermore, disproportionate ratios of patients to healthcare professionals lead to extended shifts, but with insufficient time to provide adequate care, and the ergonomic risks increase due to a high number of manual patient-handling operations. All this has become evident during the Covid-19 crisis. Often, in order to mitigate the risk of the virus spreading, health workers have been asked to maintain physical distancing measures from family members for protracted periods of time, adding to the already unsatisfactory balance between work and personal and family life. Such working conditions increase psychosocial risks exponentially and can lead to fatigue and stress.

Due to a lack of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), workers have been exposed to high levels of biological risk during the pandemic. Infection among nurses and other healthcare staff is a serious concern in and of itself, but it also has negative spill-over effects on healthcare systems, as workers who are infected or have been exposed to infection must stay away from work, thus further depleting the human resources and capacities of the system. Owing to the shortage of health workers, in many countries retired health workers and medical students have sometimes been called to duty or asked to volunteer their services.

It is worth stressing that staff shortages are not accidental and typically reflect policy choices. Many recently graduated nurses work outside the health sector due to the more competitive pay packages available to them, as well as the better working conditions and career opportunities. Furthermore, a reduction in public healthcare spending, precarious working conditions, migration (mainly from eastern and southern to western European countries) and early retirement have all adversely contributed to the health workforce shortages within the EU.

In parallel with workforce shortages, statistics show that the numbers of people choosing health and welfare careers are declining. In 2017, 13.8 % of all graduates in the EU received a degree in this field of study, but that same year only 13.6 % of all students were enrolled in one of these subjects. This means that the number of students in this field decreased by 0.2% from the previous year: a worrying trend since the number of students should increase to match the real need for health and welfare workers. There were, moreover, 2.8 times as many female graduates in this field compared to male graduates (Eurostat 2019).

The pandemic has underscored the fact that the performance of a healthcare system and the safety and health of its workforce are interrelated. ‘Flattening the curve’ as a public health strategy aimed to slow down the spread of the virus as a means of easing the pressure on healthcare institutions. It was a crisis response measure and in many ways a necessary one. But in order to foster an overall systemic resilience in the sector, OSH issues that hinder the recruitment and retention of health workers must also be addressed. Improved work environments can help to reduce stress, while decent working conditions and salaries, and investment in relevant education and skills, can support workforce retention.