Chapter Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has upended many established ways of working and living. This chapter focusses on developments of institutions of workers’ voice and assesses their readiness to cope with the current crisis and the wave of Covid-induced restructuring which has already begun.

To set the stage, we look at the current developments in democracy at work, by tracking the decline in workers’ voice and exploring the democratising effect of trade union membership and activism. We delve into the many ways in which workers’ participation and collective bargaining work together to address the complex impact of the far-reaching measures taken by companies to mitigate the disruptive effects of the pandemic. In particular, the Covid-19 pandemic has put workers’ health and safety into a harsh spotlight. While the issue of health and safety at work during the pandemic was explored in greater detail in Chapter 5 of the present issue, in this chapter we look at the role of health and safety representation as an expression of democracy at work in securing healthy workplaces.

In European multinational companies, European Works Councils (EWCs) and SE-Works Councils (SE-WCs) have a pivotal role to play in protecting and representing the interests of the European workforce not only in the immediate crisis but also in the wave of company restructuring that has already begun to sweep across the continent as a result. Drawing on the results of the 2018 survey of EWC and SE-WC members, we identify some of the deficits in EWCs’ and SE-WCs’ ability to address the impact of restructuring. Managerial attitudes towards social dialogue and particularly the use of confidentiality requirements to hobble transnational employee interest representation are key hindrances addressed here. Board-level employee representation also has a key role to play in addressing the impact of the pandemic: we chart recent developments in the gender representation gaps in boards across Europe. We also present the results of recent research into the growing Europeanisation of board-level representation in companies based in France, in which the EWCs and SE-WCs play a hitherto unexplored role.

To round out the analysis we take a critical look at who gets which share of the pie. We take a birds’ eye look at the connections between workers’ voice and the wage share. In an analysis of the excesses of the shareholder model, we find that excessive payouts to shareholders have greatly depleted companies’ financial resources over the past decade, thereby weakening their ability to weather the coming crisis.

These developments are clearly not in line with ambition of the Annual Sustainable Growth Strategy to “to restart our economies on a new, more sustainable basis” in the words of the Commissioner for the Economy Paolo Gentiloni. On the contrary, in the glaring absence of measures to protect worker’s rights in the Recovery and Resilience Facility, we seem quite far away from the understanding that social sustainability is a cornerstone of sustainability in the apparently forgotten Europe 2020 strategy (see e.g. ETUI and ETUC 2010).

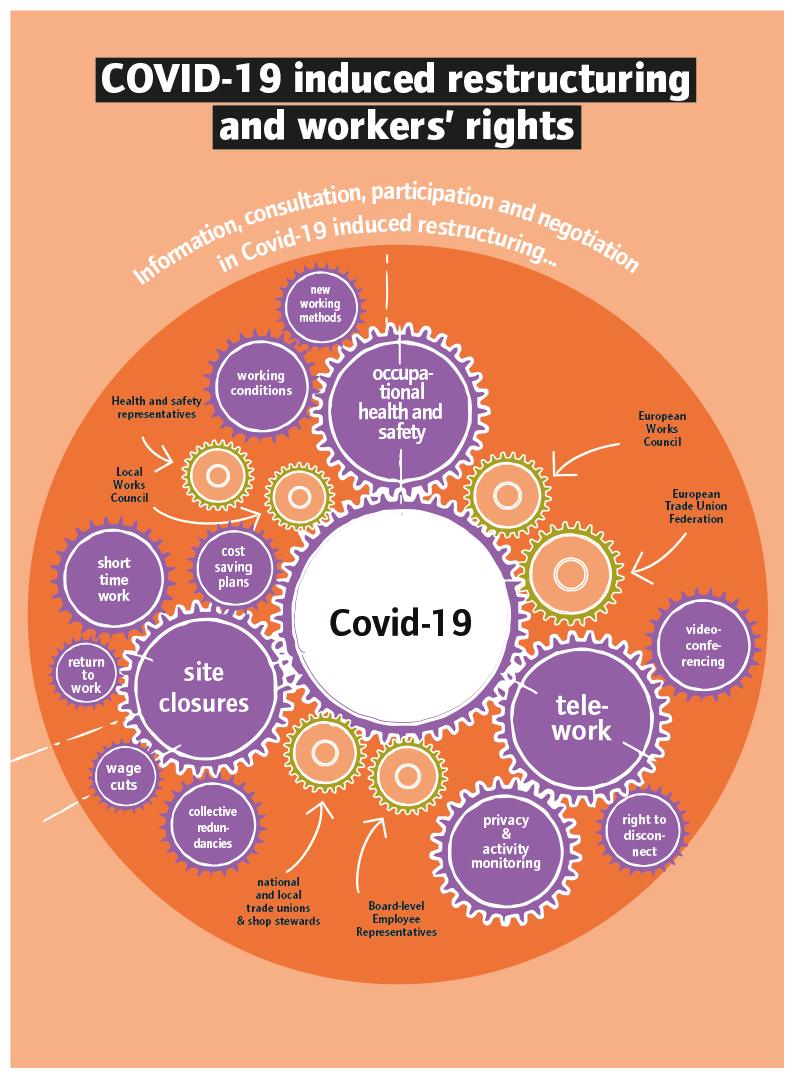

Figure 6.4 Workers’ rights in Covid-19 pandemic

Infographic by R. Jagodziński, ETUI, 2020.

Covid-19 pandemic: workers’ rights were not in quarantine

From the very beginning of the pandemic, every multinational was confronted with a need to address the potential and/or actual impact of the disease and of the accompanying distancing measures across all their sites around the globe. The measures introduced to contain the spread of Covid-19 impacted all areas of economic activity: retail, manufacturing, public services, transport, energy and utilities, construction, agriculture, and culture to name just a few. Accordingly, employee representatives at all levels of the company also needed to address the measures proposed to mitigate these impacts: local employee representatives and trade unions, health and safety representatives, board-level employee representatives, collective bargaining actors; in European-scale companies, European Works Councils and SE-Works Councils also had key roles to play in addressing the cross-border implications of measures enacted to try to stem the spread of Covid-19. This section will explore the ways in which the kinds of measures enacted by companies in response to the pandemic were (or should have been) subject to information, consultation and negotiation. None of these processes is complete by itself: different institutions of employee representation address different aspects, and in multinational companies, the European Works Council has the responsibility and competence to address the transnational dimensions of these policies and responses.

The pandemic changed everything at once

Figure 6.4 depicts some of the many interrelated issues that were thrown up by the pandemic itself and companies’ responses to it. Since the initial phase of the pandemic, sites started to be locked down in an effort to mitigate the spread of Covid-19. As a result of the closely interlocked supply-chains within and across companies in the manufacturing sector in particular, there were knock-on effects which were not immediately related to health measures: some sites had to halt their activities simply because their suppliers had been forced to close down. Essential services such as utilities and transport, both in the public and in the private sectors, had to find a way to continue to function despite the pandemic. Working from home surged in those sectors whose activities made it possible. In other sectors, such as health care and logistics, workloads increased exponentially (for more details on the impact of Covid on working conditions in the health sector, see Chapter 5). Protecting the health of those essential workers throughout the lockdown was an overriding concern, particularly in the health and public transport sectors. Once the economies started reopening, it then became a priority to ensure the safety of workers in other sectors, such as hospitality and retail. Companies, employee representatives and unions needed to manage a sudden surge in working from home, and to engage with the different national regimes of short-time work or technical unemployment schemes. As economic activity tentatively resumed, companies had to address the labour law and health and safety concerns of bringing their employees back to work, which in many cases also raised issues of whether such returns to work were voluntary or obligatory (ETUC 2020). Finally, companies began to try to manage their recovery, by initiating new restructuring plans or by accelerating plans that had already been in development prior to the pandemic (Kirton-Darling and Barthes 2020) (Eurofound 2020b) .

Where these measures had to be taken across different national sites of European multinationals, the need to accommodate sometimes significant differences in national labour law and social security regimes added additional layers and challenges to an already complex process. The task of addressing these comprehensively and coherently fell not only to management, but also to employee representatives and their unions.

Every piece of the complex machinery of multi-level workers’ participation has its place:

As illustrated in Figure 6.4, company-level responses to the Covid crisis engage all levels of workers’ participation institutions. Of course, the workplace Health and Safety representatives are front and centre in addressing the challenges and risks to workers’ health and safety which are raised by the pandemic at the workplace (see also the next page). At the local or workplace level, it is the local employee representations, such as works councils or trade unions, which are to be informed, consulted or engage in negotiations about the ways in which the companies responses to covid are implemented. Board-level employee representatives, where these exist, also have a key role to play in ensuring that the needs and interests of the workforce are taken into account at the top echelons of the company’s decision-making when company-wide strategic decisions regarding the response to the pandemic are made.

Within European-scale companies, all these adaptations to mitigate the growing crisis must take place simultaneously at all levels, increasing the need to coordinate across them. This is where the transnational level of interest representation within European Works Councils, SE-Works Councils and in many cases at the board level has a crucial role to play. This transnational level must essentially function as a bridge between national employee representations, so that the information and consultation about company responses to the Covid crisis can take place across borders and at the national level, depending on where decisions are being made and where they are being implemented. The European Trade Union Federations, which are the relevant European sectoral organisations, could draw upon a long history of support to their members active at the transnational level in EWCs and SE-WCs. Together the European Trade Union Federations compiled information briefings and advice to European Works Councils on how to address the challenges of the pandemic. The ETUC and the European Trade Union federations wrote to Commissioner Schmitt, insisting that the pandemic meant that workers’ involvement rights needed to be strengthened and enforced with more urgency than ever (ETUC et al 2020). Collective bargaining, conducted primarily at the local, regional or national levels, rounds out the picture by securing collectively agreed frameworks and solutions. The modalities of short-time work (see Chapter 2), for example, were laid down in collective agreements in many countries. (For an overview of the European legal framework for workers’ rights to information, consultation and board-level participation, see ETUC and ETUI 2017: 55)

In sum, the Covid-19 pandemic confronted an interactive multi-level system which seeks to get all the right people around the table to play their respective roles in social dialogue, information and consultation, negotiation and collective bargaining. Data on EWCs and SE-WCs also clearly shows that where trade union support is present, employee representation works more efficiently. (De Spiegelaere and Jagodziński 2019). It is too soon to tell how well this worked in practice. First evidence suggests a wide variety of responses: local and national-level employee representatives, health and safety representatives and trade unions seem to have played the roles clearly ascribed to them in the national context. At the European level, however, some EWCs were closely informed and even consulted about company-wide measures adopted, while others played no role whatsoever.